Vocal Signals Smile on the Case for Human Exceptionalism

Before Thanksgiving each year, those of us who work at Reasons to Believe (RTB) headquarters take part in an annual custom. We put our work on pause and use that time to call donors, thanking them for supporting RTB’s mission. (It’s a tradition we have all come to love, by the way.)

Before we start making our calls, our ministry advancement team leads a staff meeting to organize our efforts. And each year at these meetings, they remind us to smile when we talk to donors. I always found this to be an odd piece of advice, but they insist that when we talk to people, our smiles come across over the phone.

Well, it turns out that the helpful advice of our ministry advancement team has scientific merit, based on a recent study from a team of neuroscientists and psychologists from France and the UK.1 This research highlights the importance of vocal signaling for communicating emotions between people. And from my perspective, the work also supports the notion of human exceptionalism and the biblical concept of the image of God.

We Can Hear Smiles

The research team was motivated to perform this study in order to learn the role vocal signaling plays in social cognition. They chose to focus on auditory “smiles,” because, as these researchers point out, smiles are among the most powerful facial expressions and one of the earliest to develop in children. As I am sure we all know, smiles express positive feelings and are contagious.

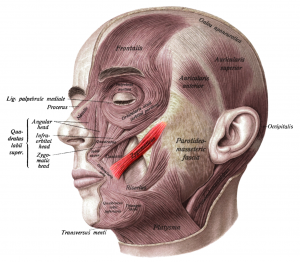

When we smile, our zygomaticus major muscle contracts bilaterally and causes our lips to stretch. This stretching alters the sounds of our voices. So, the question becomes: Can we hear other people when they smile?

Figure 1: Zygomaticus major. Image credit: Wikipedia

To determine if people can “hear” smiles, the researchers recorded actors who spoke a range of French phonemes, with and without smiling. Then, they modeled the changes in the spectral patterns that occurred in the actors’ voices when they smiled while they spoke.

The researchers used this model to manipulate recordings of spoken sentences so that they would sound like they were spoken by someone who was smiling (while keeping other features such as pitch, content, speed, gender, etc., unchanged). Then, they asked volunteers to rate the “smiley-ness” of voices before and after manipulation of the recordings. They found that the volunteers could distinguish the transformed phonemes from those that weren’t altered.

Next, they asked the volunteers to mimic the sounds of the “smiley” phonemes. The researchers noted that for the volunteers to do so, they had to smile.

Following these preliminary experiments, the researchers asked volunteers to describe their emotions when listening to transformed phonemes compared to those that weren’t transformed. They found that when volunteers heard the altered phonemes, they expressed a heightened sense of joy and irony.

Lastly, the researchers used electromyography to monitor the volunteers’ facial muscles so that they could detect smiling and frowning as the volunteers listened to a set of 60 sentences—some manipulated (to sound as if they were spoken by someone who was smiling) and some unaltered. They found that when the volunteers judged speech to be “smiley,” they were more likely to smile and less likely to frown.

In other words, people can detect auditory smiles and respond by mimicking them with smiles of their own.

Auditory Signaling and Human Exceptionalism

This research demonstrates that both the visual and auditory clues we receive from other people help us to understand their emotional state and to become influenced by it. Our ability to see and hear smiles helps us develop empathy toward others. Undoubtedly, this trait plays an important role in our ability to link our minds together and to form complex social structures—two characteristics that some anthropologists believe contribute to human exceptionalism.

The notion that human beings differ in degree, not kind, from other creatures has been a mainstay concept in anthropology and primatology for over 150 years. And it has been the primary reason why so many people have abandoned the belief that human beings bear God’s image.

Yet, this stalwart view in anthropology is losing its mooring, with the concept of human exceptionalism taking its place. A growing minority of anthropologists and primatologists now believe that human beings really are exceptional. They contend that human beings do, indeed, differ in kind, not merely degree, from other creatures—including Neanderthals. Ironically, the scientists who argue for this updated perspective have developed evidence for human exceptionalism in their attempts to understand how the human mind evolved. And, yet, these new insights can be used to marshal support for the biblical conception of humanity.

Anthropologists identify at least four interrelated qualities that make us exceptional: (1) symbolism, (2) open-ended generative capacity, (3) theory of mind, and (4) our capacity to form complex social networks.

Human beings effortlessly represent the world with discrete symbols and to denote abstract concepts. Our ability to represent the world symbolically and to combine and recombine those symbols in a countless number of ways to create alternate possibilities has interesting consequences. Human capacity for symbolism manifests in the form of language, art, music, and body ornamentation. And humans alone desire to communicate the scenarios we construct in our minds with other people.

But there is more to our interactions with other human beings than a desire to communicate. We want to link our minds together and we can do so because we possess a theory of mind. In other words, we recognize that other people have minds just like ours, allowing us to understand what others are thinking and feeling. We also possess the brain capacity to organize people we meet and know into hierarchical categories, allowing us to form and engage in complex social networks.

Thus, I would contend that our ability to hear people’s smiles plays a role in theory of mind and our sophisticated social capacities. It contributes to human exceptionalism.

In effect, these four qualities could be viewed as scientific descriptors of the image of God. In other words, evidence for human exceptionalism is evidence that human beings bear God’s image.

So, even though many people in the scientific community promote a view of humanity that denigrates the image of God, scientific evidence and common-day experience continually support the notion that we are unique and exceptional as human beings. It makes me grin from ear to ear to know that scientific investigations into our cognitive and behavioral capacities continue to affirm human exceptionalism and, with it, the image of God.

Indeed, we are the crown of creation. And that makes me thankful!

Resources

- “Brain Synchronization Study Evinces the Image of God” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Can Evolution Explain the Origin of Language?” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Darwin’s Problem: The Origin of Language” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “Speaking of Adam and Eve: Study of Languages Supports Biblical Account of Human Origins” by Fazale Rana (article)

- “One of a Kind: Three Discoveries Affirm Human Uniqueness” by Fazale Rana (article)

Endnotes

- Pablo Arias, Pascal Belin, and Jean-Julien Aucouturier, “Auditory Smiles Trigger Unconscious Facial Imitation,” Current Biology 28 (July 23, 2018): PR782–R783, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.084.